2 February 2012 Interview: Trevor Horn

‘That coldness; that precision’: Simon Price meets the man who invented the eighties

There’s a moment in ‘The Troggs Tapes’, the sixties band’s legendary studio outtake, in which drummer Ronnie Bond, during a heated debate over the sound of their new single, argues, in a richly agricultural accent, “You’ve got to put a little bit of fucking fairy dust over the baaastard.”

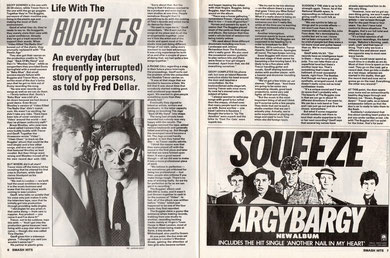

If any man on earth knows all about putting a little bit of fucking fairy dust over the bastard, it’s Trevor Horn. If you hear any record from that golden period between punk and Live Aid which shimmers and sparkles and seems to fly above the earth, it was either produced by Trevor Horn (see: The Buggles, ABC, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Grace Jones, Dollar, Pet Shop Boys, Propaganda, Malcolm McLaren and countless others), or trying to sound as if it was (see: pretty much everyone else). The immaculate cleanliness of what Paul Morley christened ‘the new pop’ was Horn’s handiwork. He is, essentially, the man who invented the eighties.

Lenses as thick as milk bottle bottoms, he relaxes on a brown leather sofa in the loft of his own Sarm Studios, the converted Notting Hill church whose history dates back to legendary seventies sessions by Led Zeppelin and Bob Marley And The Wailers. It’s very much a working studio: intermittently, the conversation is disrupted by thunderous bass explosions from the floors below, and he explains “Sorry, that’s The Prodigy recording their new album.”

The pretext for talking to Horn is his involvement in 30/30, a collaborative project between the EMI label and the Roundhouse venue which offers unsigned artists the chance to work with top producers for free (Trevor’s recorded a track with 22-year-old Londoner Azekel), but at any given time, Horn has several plates spinning. He’s just announced, for example, that his old band The Buggles will go on tour for the first time ever in 2012.

“I’m keen to get out on the road and play live,” he says, smiling and habitually squeaking his shoes together as he speaks. “I’ve been stuck in a studio for 30 years. The Buggles never played live at the time! That was the joke. When that thing [he means ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’] was a hit, I’d been a bassist for years, I’d played on all kinds of things…”

Born in 1949, Horn’s early life, growing up in Durham with schoolteacher father and a mother from a mining family, could barely have been further from the swing of things.

“I didn’t come to London till I was 21, and it was a different world then: all these ballrooms like the Hammersmith Palais would have a DJ, but they would also have a band. And it was a way to earn a living as a musician. Two nights a week, the ballroom dancing would stop, then we’d play whatever was in the charts. I could read music, and I could play bass, which was a very new instrument in the early seventies, so if you could do those two things, you could make a living. And I was really stupid and I used to behave badly and get drunk and do all kinds of silly things because I was bored out of my mind.”

That boredom proved productive.

“When I got to 25 I left London, went back to the provinces and built a recording studio — me and another guy, with our bare hands. And I started fixing up other people’s songs — people who’d won a local songwriters’ competition, and someone said to me, ‘You know, what you’re doing is called being a record producer.’ I’d seen that credit on records but I never knew what it was. And I just had this moment where I knew that was what I was going to do. From that moment, it took me six years to get my first hit, and I earned my living playing crap and whatever.”

That “crap and whatever” included an album with CBS-backed flop John Howard, and his own “sci-fi disco” project Chromium, whose single ‘Caribbean Air Control’ featured an early example of Horn’s sonic inventiveness.

“This was ’77, and I made a ‘drum machine’ using tape and getting my drummer to play fours,” he says. “People would say, ‘It sounds like fuckin’ machines!’ and I’d reply, ‘That’s exactly the point!’”

Even though punk was going on around him, Horn was never a convert. “Being a muso, it wasn’t easy to be a fan of punk. Although I think I became more of a fan of punk when I was in America in 1982, and I got so angry with American radio, and then ‘Should I Stay Or Should I Go’ by The Clash came on the air and I had tears in my eyes. I thought, ‘It’s so crap, it’s fantastic!’”

Nevertheless, in a roundabout way, the punk explosion did affect Horn’s thinking. “In the seventies there were rock gods — Elton John, Rod Stewart — everyone sounded fabulous, everyone could sing really well, and it was daunting. Then the punk thing happened, and I thought, ‘If people will listen to that, what am I afraid of? I can do anything!’”

Horn wasn’t a lover of disco either, despite a stint playing bass for producer Biddu and his protégée Tina Charles, of ‘I Love To Love’ fame.

“I hated that shit,” he remembers, “but that’s what I played. I was Tina Charles’s boyfriend for a while. I learned a lot from her. Tina came home one night with the first backing track from a professional producer I’d ever heard. I’d tried making my own backing tracks but they sounded wrong. Biddu knew what he was doing: the drum machine was tight, everyone played exactly what he told them to, it was all really well put together. And I played it all night, thinking that’s what I’m trying to get to: that coldness, that precision.”

Horn’s dreams of being a renowned session man were starting to fade. “I flirted with jazz rock. I wanted to be Stanley Clarke. Tina Charles told me that if I practised for every minute left in my life I would never be as good as Stanley Clarke, and that all I was was a loser.”

However, it was while he was on Charles’s payroll that he and bandmates Geoffrey Downes (keyboards) and Bruce Woolley (guitar) conceptualised what would become Horn’s ticket to stardom: The Buggles.

The Buggles, ‘I Am A Camera’

“The idea came about because Bruce and I loved The Man-Machine by Kraftwerk, and the records Daniel Miller was making as The Normal — ‘Warm Leatherette’. We even read JG Ballard’s Crash because of that. It was an interesting time, you could feel something was coming in the eighties. We had this idea that at some future point there’d be a record label that didn’t really have any artists — just a computer in the basement and some mad Vincent Price-like figure making the records. Which I know has kinda happened, but in 1978 there were no computers in music yet, really. And one of the groups this computer would make would be The Buggles, which was obviously a corruption of The Beatles, who would just be this inconsequential bunch of people with a hit song that the computer had written. And The Buggles would never be seen.”

That hit song, ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’, took a while to materialise. “We had the opening line for ages — ‘I heard you on the wireless back in ’52’ — but couldn’t figure out the next line. Then one afternoon we were chatting and it just came — ‘lying awake intently tuning in on you’ — because we were talking about Jimmy Clitheroe and Ken Dodd and the classic age of fifties radio comedy. And I’d read The Sound-Sweep by JG Ballard, and some of that was in there — the abandoned studio, ‘rewritten by machine on new technology’… ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’ just popped out.”

Released in September 1979, the fiendishly catchy single was a number one across the world (and, famously, became the first song ever played on MTV). Suddenly, at the age of 30, Trevor Horn was a pop star.

Regarding never touring, he says: “We were eminently able to play live — we were musos and ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’ was relatively easy to play. What held us back was we went all over Europe promoting that single, then the follow-up ‘Living In The Plastic Age’, then we met Yes!”

In one of the most incongruous transfer deals of the eighties, the sugary synth-pop act were swallowed up by the monsters of prog rock, who had a vacancy for a singer and a keyboardist.

“Suddenly I was impersonating Jon Anderson in front of 24,000 people,” says Horn. “When someone offers you something like that, c’mon, you’ve got to do it…

It was a great experience. And it makes you a bit fearless in a recording studio. What else can life throw at you?”

Life in a touring stadium rock band wasn’t to Trevor’s liking, and after seven months he quit. Downes, however, stayed on board. “Geoffrey had had a taste of something other than novelty hit pop-dom, and he wanted to go and rock. And I didn’t blame him. The choice between staying in The Buggles and selling five million albums with [supergroup] Asia, as he went on to do, was an easy decision.”

ABC, ‘The Look Of Love’

Adventures In Modern Recording, the second Buggles album, was practically a Trevor Horn solo effort. Considered a cult classic by aficionados of studio-craft, it was a commercial failure. “I think the songs are terrible,” he admits, “but the production is great.” By the time of its release, however, Horn had already found his vocation: producing records for other acts.

“It was kind of unconscious,” he continues. “My wife [Jill Sinclair] owned a studio. And when Geoffrey left The Buggles, Jill became my manager. She said, ‘My first bit of advice is that as an artist, you’ll only ever be second or third division, however hard you try. But if you go into production, you’ll be the best producer in the world.’ She was quite purposeful. And the first thing she suggested was Dollar. I said, ‘Why would I wanna work with Dollar!? A cheesy pop duo.’ And she said, ‘Do a Buggles record, but have them front it.’ So I met them, and that’s exactly what they wanted.”

The saccharine duo of David Van Day and Theresa Bazar were all but washed-up till Horn took them on as his playthings and used them, on a run of singles including the sublime ‘Hand Held In Black And White’, as a vehicle to showcase his ideas.

“There was something sweet about them — these little people living in this techno-pop world — and we wrote ‘Hand Held In Black And White’ on the spot. The same afternoon we wrote ‘Mirror Mirror’, which was about them looking at each other. I thought it came out well, but I never thought much about it until I ran into Hans Zimmer [Hollywood composer and Buggles collaborator], who said, ‘I heard your record with Dollar, it’s really good,’ and loads of people seemed to like it. Then an astounding thing happened: the NME liked it! Paul Morley liked it. And then I was on a roll. It was epic. I only did four songs, and the final one, ‘Videotheque’, was about them seeing themselves on film. So it was like a little opera.”

The Dollar project led onto Horn’s masterpiece, ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love.

“My wife found ABC, again. She was looking for a bright young band, and they were smart guys. And they were hilarious. They said to me, ‘If you work with us, you’ll be the most fashionable producer in the world, because this week, on Thursday, we were the most fashionable band in the world.’ They went to this club in Sheffield, where they were at university, and they used to dance to soul records, and they wanted to make their soul record. It took me a bit of time to get what they wanted, because to me, it was disco. But it was disco a generation on.”

Horn says that “samplers were just starting to come in on that album” and indeed he and his team were pioneers of the use of sampling in pop.

“Geoffrey had one of the first Fairlights [a digital sampling synthesiser] that made it to England. We used them on the second Buggles album, and with Yes on Drama. I think we were the first people to put a human’s voice in it, on Dollar’s ‘Give Me Back My Heart’.”

Given that Horn’s aim was “coldness and precision”, the sampler was the perfect tool.

His next big project was Duck Rock with Malcolm McLaren, who had just discovered the black American craze for scratching — a technique of ad hoc ‘sampling’ which must have seemed strangely primitive next to the Fairlight.

“That’s what drew me into it!” he says. “At first, Malcolm was talking about ‘world music’. All that South African stuff that Paul Simon took up later, we were there two years earlier on ‘Double Dutch’. But Malcolm said, ‘In New York the black kids scratch European techno records.’ And I was like, ‘What? Don’t they like soul music?’ He said, ‘Nooo! They’re into Kraftwerk and Depeche Mode!’ And it was all starting to kick off. The first time I heard scratching was on ‘Buffalo Gals’, and I thought it was fucking amazing. It was the same thing as the Fairlight, really. What a great guy Malcolm was. If he grabbed onto an idea, you couldn’t stop him, even if it seemed so hopeless at times. You could listen to him talk for hours. I remember being sat on a New York street with Malcolm and [engineer] Gary Langan, going there at lunchtime, and the next time I looked at my watch it was eight o’clock in the evening.”

In 1983, Horn reunited with Yes, this time as a producer for the album 90125, featuring one of his most revered creations: ‘Owner Of A Lonely Heart’, a berserk piece of sliced-and-diced symphonic metal.

Grace Jones, Slave To The Rhythm

The Art Of Noise, the entirely electronic act Horn formed with Gary Langan, Anne Dudley, programmer JJ Jeczalik and journalist Paul Morley, grew from those Yes sessions. They were the first band on ZTT, the Futurist-inspired label Horn set up with Paul Morley. It was a strange union: the studio boffin and the arch-conceptualist.

“I didn’t realise what music journalists did,” says Horn. “Not really. Then I kind of got it with Paul. What they do is romanticise us. And there’s a need for that, because I’m not really going to romanticise myself. So I thought Paul would be an exciting guy to start a label with. And it was exciting for a while. The problem with record labels, however, is that when you start, everybody wants your input, but the minute the artists are established, they want you out of the way. And it’s ‘theirs’. If you wanna hang on in there, you need to be more pragmatic. And Paul, in 1984, was mental. He and my wife Jill would fight like hell, and I had to be in the middle of that. But out of that comes friction, fire…”

ZTT’s biggest success, by far, came after Horn spotted a quintet of pervy Scousers in leather jockstraps on television.

“I’d had a big row with Yes and I wasn’t speaking to anybody in the band. Then this group called Frankie Goes To Hollywood came on The Tube and Chris Squire [Yes bassist] said, ‘They look like the sort of band you should have on your new record label.’ I can’t remember being particularly smitten by the song, but what I did like was the drummer — the way he was playing four-on-the-floor. And then I was driving home listening to David Jensen on Radio 1, and he played a session of ‘Relax’. And the song was all about gay sex, but they were being ever-so-polite when he interviewed them. I came in and I said to my wife, ‘I think we should sign this band called Frankie Goes To Hollywood.’ I remember meeting them, and they said they wanted to sound like a cross between Kiss and Donna Summer, and I thought that was great.”

Frankie’s first single, ‘Relax’, was one of the biggest-selling singles of the decade (with the unwitting assistance of a “ban” from Radio 1’s Mike Read), and pioneered the format of the multiple 12”.

“We ‘performed’ the 7” version — the band playing their instruments, JJ on the Fairlight, me operating the drum machine, altering it as we went along. Then we did a version for 14 minutes that we called the Sex Mix that I did some pretty gross things over — just fucking around — and it didn’t have the song anywhere in it. The first 10,000 12”s that came out didn’t have the song: they just had ‘Ferry Cross The Mersey’, the Sex Mix, and a Paul Morley interview on the back. And we got LOADS of complaints, particularly from gay clubs who were angry about some of the noises on the Sex Mix.

“The record had been out for a few weeks and it wasn’t doing much. Then I was in New York with [then-Island Records boss] Chris Blackwell, and he took me clubbing to Paradise Garage, which really opened my eyes. The DJs — the New York Citi Peech Boys — were playing records including a lot of my 12”s, like the ABC ones, but they also had projectors and drum machines and synths, and it was huge. And when I saw that, I realised I needed to go and do another mix of ‘Relax’ so it would go over at a place like that — ’cos when you play it really loud, through those bins, you barely need anything else but the drum machine. So I went to the Hit Factory in New York, and the engineer there… I could tell he didn’t like it and I had to really push him, saying, ‘Look, I know this is all drum machine, but that’s what you have to do to make it work. Push that there, push this here.”

The Art Of Noise, ‘Moments In Love’

Not everyone got the Frankie thing, especially Stateside.

“I remember I was working with Foreigner when ‘Relax’ came out, and someone sent over the video — you know, the pissing one. Foreigner said, ‘You think this is GOOD!?’ And I was like, ‘Um, yes I do, actually! Although I wasn’t expecting the pissing…’”

Another eighties tour de force was Horn’s one-off collaboration with cuboid-headed, chat show host-slapping fembot Grace Jones.

“Grace was a trip. I only did one track with her, ‘Slave To The Rhythm’, but I got a bit carried away and did six different versions. When she did that song at my Prince’s Trust Concert at Wembley in 2004, it was such a moment: I saw hardened musos in the band with tears in their eyes. But when I asked her to do it, she had a right go at me about how I never return her calls, how she hated the music business, and at the end of it all I said, ‘Sorry, but will you do this show?’ She said, ‘I’ll do it, but it will cost you.’ I said, ‘Cost me what? From my pocket? From my soul? From whatever else?’ And she said, ‘ALL OF THEM!!!’”

I wonder whether Horn consciously distinguishes, in his own mind, between records where he’s simply doing a professional job and records where he’s creating art.

“It’s an interesting question,” he says. “They’re all pop records, really, and they’re either hits or they’re not. ‘There You’ll Be’ by Faith Hill is a very good record, but it’s completely different from ABC. But there was a point in the eighties where I suddenly just stopped messing around with all the sampling stuff. I’d had enough of it. There was too much of that stuff by that point anyway, and everyone was all over it.”

One of Horn’s biggest post-eighties successes, Seal’s ‘Kiss From A Rose’ (for which he won a Grammy), is also one of his most conventional.

“Yeah, well I don’t determine those things. The song determines it. ‘Kiss From A Rose’ was unusual. It reminded me of a song from the sixties or something. I always try to make records that aren’t going to date too quickly, because if you do records that are exactly what’s now, and make the song fit into some sort of… new brutality, it doesn’t work. ‘Kiss From A Rose’ is meant to be normal and lovely. The originality comes in all that stuff he does: [sings] ‘Baby!!!’ in amongst that funny old folk song vibe he’s got going on. And he had all that in his head. I grabbed it as fast as I could.”

One of Horn’s most eyebrow-raising hook-ups in recent years was Belle And Sebastian’s Dear Catastrophe Waitress in 2003: the master of hi-gloss studio sheen meets the icons of ultra-schmindie lo-fi.

“I know, but I loved that song of theirs, ‘Stars Of Track And Field’. My daughter used to play it all the time. And my PA in LA, a girl called Marianne, did their caravan at Coachella, and she set it up. They’d had a bad experience with a producer, and I thought, if they’re gonna be produced, I don’t want anyone to spoil them, you know what I mean? The album after Dear Catastrophe Waitress I didn’t like as much, because I thought the guy tried to make them sound like something, whereas I just tried to get the best version of them.”

And then came a two-headed pseudo-Sapphic pop phenomenon called T.A.T.U.

“I went to see [Interscope chairman] Jimmy Iovine, who’s a real character. He played me the Russian version of ‘Not Gonna Get Us’ by T.A.T.U. and I loved it. He said it was the first time he’d sold a million records in Russia, which probably meant 40 million, because most of them don’t get accounted for. They asked me to write an English lyric, and I sat down with the Russians, which was daunting. So I wrote ‘All The Things She Said’, and I was gonna imply it was more of a teenage infatuation rather than embarking on a lifetime of… whatever.”

Weren’t they really lesbians, then?

“Naaaah! They weren’t really 14, either! They were under 20, which in music business terms means you can get away with it. But they were great girls; a good laugh. As my daughter said, ‘They snogged their way across Europe.’”

There are so many other records we haven’t had time to discuss. I’m kicking myself for not mentioning Marc Almond’s Tenement Symphony album or Propaganda’s ‘Dr Mabuse’ single. As I hand him my copies of the fairy dust-coated ‘Hand Held In Black And White’ and a rare ‘Relax’ white label to sign, I wonder how he’s avoided burning out.

“I have a really good team,” the über-nerd genius says, peering up through those milk bottle specs. “We’re diligent. We don’t go to the pub in the evening. We’d rather work on some vocals.

[www.thestoolpigeon.co.uk/]